The Project

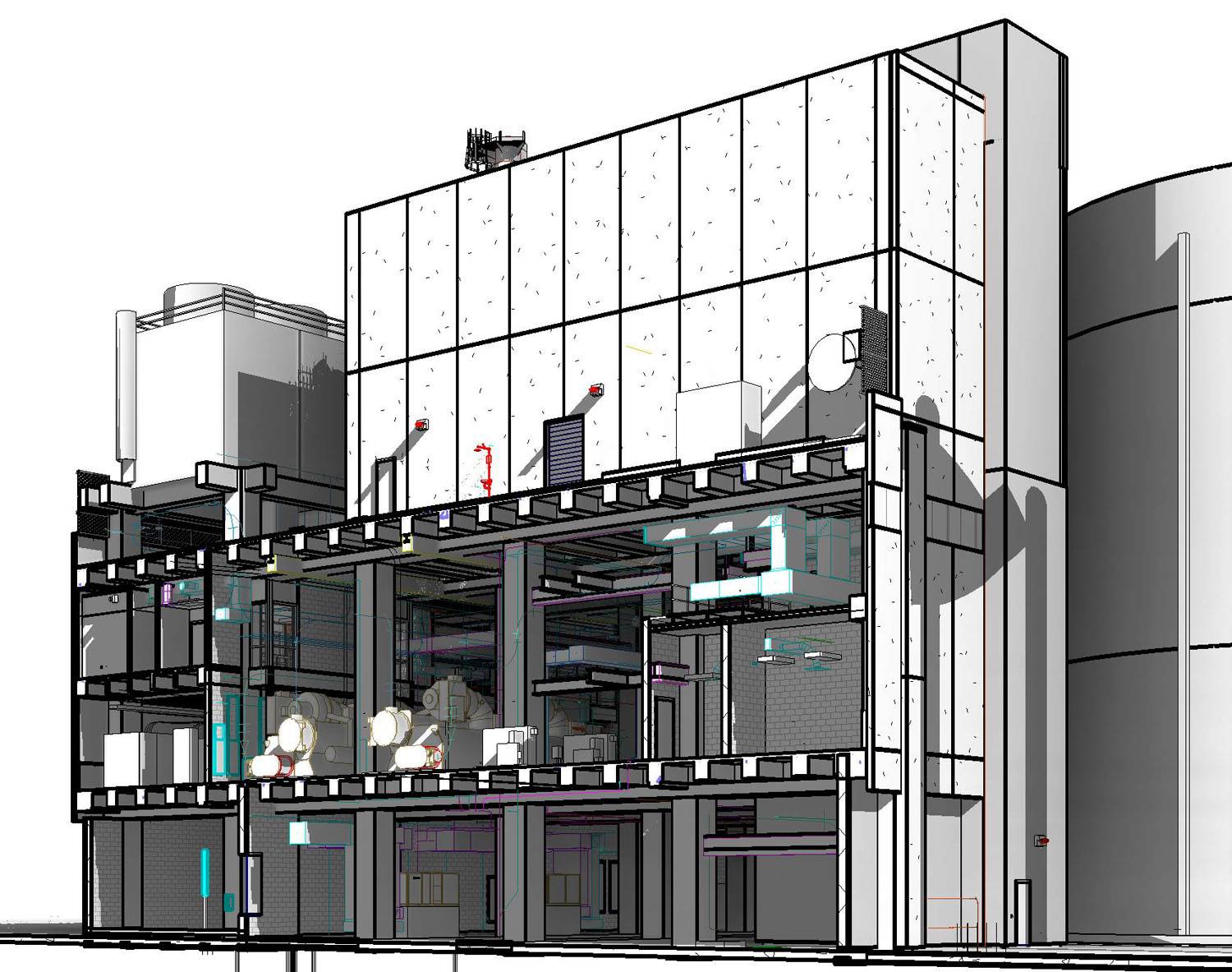

The biggest project that we have in the office right now, in terms of sheer tonnage, is the East Plant at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. It's a giant concrete frame clad in brick and concrete panels that houses heavy steel pipes and equipment filled with water. Seriously, the gross weight of the building is probably in the tens of thousands of tons. It will outlast everyone alive today.

It's a thermal energy plant, which in layman's terms -- this is a good sentence to skip if you're a mechanical engineer -- means that it chills and heats water to run the cooling and heating systems of the campus. It needs to be very durable, given the critical nature of the buildings it serves, which includes hospitals and clinics. The building also needs to be reasonably inexpensive and attractive enough in sort of a rugged way. It's not an architectural bellcow, nor is it intended to bein this case. It's a good worker that doesn't attract attention.

What Is Precast, Anyway?

Precast concrete (just "precast," to those of us in the biz) is pretty good at being durable, seeing as how it's concrete. So that's what makes up a large part of the building's skin. Precast concrete is just concrete that's made in a plant and then shipped to the site for installation. That lets the manufacturer do a better job of it -- they have more control over dimensional tolerances, the materials that go into it, and how it's formed and cured. That means that precast is typically a stronger, more uniform product than site-cast concrete, and its appearance can be a lot more flexible. You've seen it all over the place. The Texas Department of Transportation has thoughtfully and comprehensively explored just how ugly precast can be in the overpasses and highways of the state; recent projects like the Perot Museum in Dallas have pushed boundaries in other directions.

During construction, architects are typically engaged to observe construction and make sure that it's going in accordance with the plans. Part of that, here, is to make sure that the precast is matching up with the samples that we and the university approved. So a trip to the plant was in order.

The Process

Concrete starts out as a mixture of cement, water, and aggregate, which is a fun word for "a bunch of sand and rocks." It starts out pretty wet and fluid. Pouring concrete is usually literally just that: dumping a semi-fluid mix of the stuff into something that will hold it in place (formwork) until it hardens. That hardening process is called curing.

It's not so simple as that, of course. The mixture I mentioned earlier is pretty strong if you're just putting heavy stuff on it, but if you tried to bend it, it would fracture pretty easily. Bending is a big deal for buildings. Imagine putting an elephant on the end of a cartoon seesaw. It bends, right? Well, that's essentially what goes on in the columns and beams of a building. We use steel reinforcement to make concrete strong to deal with the forces that happen with bending, too.

Precast plants turn out precast by the millions of tons. One of their tricks is something called a casting bed, which is a long table that supports formwork. The forms can be easily moved around to make different sizes and shapes of panels. Most of this takes place inside a huge shed, because the last thing you want is rain on your wet concrete. Then it becomes really wet concrete, which then becomes trash.

Moving Stuff

Have I mentioned that concrete is heavy? This particular piece -- bound for our project -- weighs in at nearly 20 tons. A significant amount of the equipment in the plant is dedicated to moving heavy things. A bridge crane is used to pick up the pieces from the casting bed, and giant mobile framework-like cranes move the pieces around the yard.

The yard is huge. Precast takes up a lot of space, and it needs to be stored until it's needed at the jobsite. Precast will be stockpiled as it's produced for a particular job, placed carefully in a particular sequence on flatbed trailers, then hauled to the site where it's frequently picked up off the trailers and placed directly onto the building. It's attached by welding embedded steel plates to more plates embedded in the concrete frame of the building.

Design and Time

Precast falls in a bit of an odd part of the spectrum when it comes to truth about materials. It isn't a natural material -- you won't find very much in nature that resembles modern precast. It can mimic certain types of stone, but without the character. One of the basic tenets of good design is "don't try to make things look like other things." Precast's appearance is more fluid than many other materials, and that's a hazard for those who hold to the perspective that inventiveness should be the calling card of all human work.

With some notable exceptions, concrete is usually best a foil. It is the basis and foundation for lighter works; it is the straight man whose honest solidity gives bearing to the comedian's fancy. Only a deft hand can coax more truth from concrete than that.

Lasting

The truth is that concrete is about mass and solidity even moreso than many other massive and solid materials, like stone. The precast yard makes that clear: its most salient characteristic is acre upon acre of whited slabs, a temporary graveyard awaiting a sequential unearthing by rolling steel frameworks to be hauled hundreds of miles across the country. If our buildings are eaten by time, it will not be steel, which rots, or stone, which is little used, or glass, which shatters, to mark our place. It will be concrete: billions of tons of hardened sand. This yard will have poured out as much of that evidentiary gravestone as any place.