Introduction

Front image: By NASA/GSFC (Atlanta, United States) [Public domain or CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. Infrared image of Atlanta.

The latest entry in the Collateral Design series tackles a timely topic, given that we're in the middle of our annual mid-September heat wave: thermal comfort and its meaningfulness to life, architecture, and everything. It also includes slant references to Ben Franklin's finest literary work. Bonus points if you catch those.

The latest entry in the Collateral Design series tackles a timely topic, given that we're in the middle of our annual mid-September heat wave: thermal comfort and its meaningfulness to life, architecture, and everything. It also includes slant references to Ben Franklin's finest literary work. Bonus points if you catch those.

Brantley Hightower, 7/18/2011

So at the end of the day on Friday, the bearings on our indoor fan unit seized up, reducing our air conditioning system to a loud but ultimately ineffectual piece of machinery. While it seems like air conditioning repair companies could make a killing by doing repair work on the weekends, my wife, child, and I ended up spending the weekend with the inside temperature considerably warmer than normal.

One of the things we were required to read in architecture school was Lisa Herschong's "Thermal Delight in Architecture." In this compelling little book, the argument is made that mechanical systems have allowed a building's thermal qualities to be always consistent but that this eliminates a potentially compelling design tool. While we may like the color green, a house in which everything is painted green is ultimately quite monotonous. Herschong argues the same could be said of a house which is constantly kept at 72°.

While there are obviously some limits to this argument, I must say my house has has been much more livable without air conditioning than I would have thought. And while it did get unbearable in the afternoons, I was surprised at how accommodating my body was as the indoor temperature climbed into the 80s. With fans spinning in each room (and with my in laws' house as a convenient refuge) I could imagine living through a Texas summer with considerably less mechanical intervention. There would definitely be more perspiration involved and "delight" would probably not the a term I would use often in mid August, it was a much more plausible proposition than I would have thought before the weekend.

Of course, if that were the option I would have wanted to make a few changes to the design of my house. It has been interesting to experience the thermal particularities of my 1954 abode -- for example, the south facing bedrooms are considerably warmer in the evenings than the north-facing living rooms -- but with its many large operable windows it performed remarkably well.

As interesting as this experiment may have been, we of course would have kept the AC humming throughout the weekend if that option had been available. And that, I suppose, is the rub of this equation. While we can live a life less dependent on mechanical system, so long as they exist there will always be a strong desire to use them.

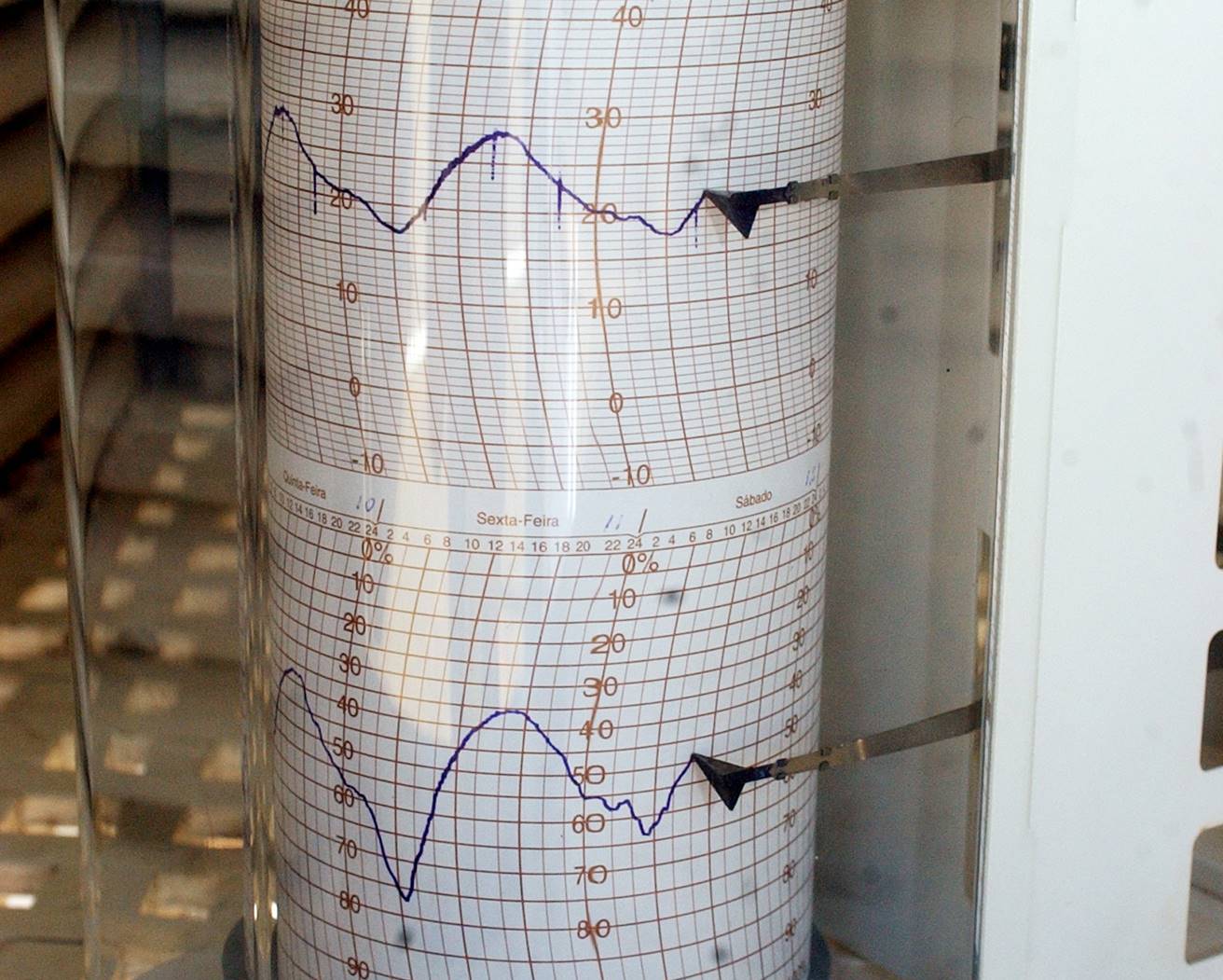

By José Cruz/ABr (Agência Brasil [1]) [CC BY 3.0 br (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/br/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons. Machine for measuring humidity.

Jay Louden, 7/25/2011

Thermal Delight. Only a 20th-century Westerner, preferably one from California, could possibly look at the unallayed scorch and freeze of the world unconditioned and see such tragic loss. Unenlightened people would instead see the drop in mortality and rises in productivity and comfort that those machines give us, and think they're just the thing, and also, wouldn't it be nice if we could drop a bubble over the city (page 20 in my paperback version of Thermal Delight, if you're playing along at home).

This may be shocking to hear, but I think it's more complicated than the two versions I just presented. And I think your conclusion about how you would have used the air conditioning if it had been available, in spite of your surprise at the thermal performance of the house and soft spot for TDIA, is a perfect example. Expecting people to change their behavior because of what you (not you, Brantley, but a random "you," preferably a Republican) value, rather than what they value, is a waste of time (and frequently life, if you happen to be of the profoundly religious bent). That is, Ms. Herschong's delightfully crafted prose is only a foil for actual human choices, not a guiding light for humanity. Which is to say that I don't like being hot.

I'll elaborate with my own example. I particularly enjoy seasons, even if I don't enjoy all of them. Like, for example, summer. But the long, slow curve into fall -- the heat, still enveloping, loosens; the sun fights its way up each day but is a giant engine slowly spooling down -- makes me glad. A cold front will bluster through and bring two nice days before it is caught by the fading sun, and there will come a day well in fall when the smell of a roasting turkey in the cool, still air of my house can bring a tear to my eye.

But I can enjoy these things in part because I run the air conditioning. How can one say that that's a less valid choice than to do without, or to live life enveloped in humidity-controlled 72-degree bubble? Only by applying a value system which is aligned in that way. To expect life to lose its richness as though blown away by an air handler, or for the challenges of a Texas summer to impart a glazing of sweetness to the run of days, is a misapplication of morals to climate control.

So, I say to you, Brantley, condition proudly! Preferably with an 18-SEER unit for efficiency, and you should consider keeping it around 80, and are you sure you can't fit any more insulation in the comically small attic of your 1954 abode? But proudly!, because your life is worth living no less even if it's comfortable. At least in a thermal sense; if you were really going for comfortable you'd find another profession. But that's for another day.

By NOAA (Brookhaven, New Mexico) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Approaching thunderstorm with lead gust front. Rain-cooled air from the storm moves out ahead of the storm. It ploughs under the warm moist air forming a flat "shelf cloud."

By NOAA (Brookhaven, New Mexico) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Approaching thunderstorm with lead gust front. Rain-cooled air from the storm moves out ahead of the storm. It ploughs under the warm moist air forming a flat "shelf cloud."