Introduction

We could have started here, I suppose, in this resuscitation of Collateral Design with a series of writings about principles. But we didn't, mainly to give some context to this exchange, which lies at the heart of this series of back-and-forth about architecture, meaning, and philosophies about what we intend to accomplish with architecture.

Jay Louden, 1/16/2011

Everyone has values and intentions, honorable or otherwise, that they use to make decisions. Some of them are well-reasoned; some of them are morally questionable; some of them are bound to failure from the start. Like, for example, "no puns in future Collateral posts." Design is nothing if not decision-making, so designers operate by principles, too. I'm going for an inclusive definition, here, so I'm going to call things like "make the client happy no matter how unfortunate that brick is" and "maximize profit at the expense of everything else" principles, too. Some principles aren't principled.

Where I take issue with a lot of architectural work, mine included, is that the principles aren't usually stated explicitly. Design decisions are made by applying to immediate aesthetic or functional -- and entirely logical -- reasons rather than being guided by deeper, more general parameters. It might surprise people who know me, but I don't trust logic. Not one bit. It can be too easily manipulated by initial assumptions and the availability of information (the concept of access-limited logic, basically) to yield conclusions which are internally consistent but entirely wrong once a wider sphere of information is available.

Sorry. That got kind of pointy-headed. In essence, all I'm saying is that if you start off in the wrong direction, reason isn't necessarily going to get you back on track. So that's why I think it's worthwhile to establish a set of principles at the beginning, because -- to continue the direction-based analogy -- then you have a destination in mind at the outset, and you can measure your progress by that destination. Establishing principles can mean a lot of things, and it doesn't have to be some philosophically complex, wholly theoretical mishmash of abstruse concepts communicated through an odd mixture of invented language and French words like a certain professor of mine espoused. Principles can be something like "express the qualities of stone." Or "simplicity." Or "I really wish it were still 1985."

This approach, which I'm proposing but have rarely enough yet practiced, seems like it's pretty simple. It's not. In fact, it makes the process of design more elaborate, because it places a layer of assessment on top of the more pragmatic and individual decisions designers have to make. If you're trying to design a project which is all about stone, what does that say about how the rooms are laid out and shaped? What does that say about the roof? And if you come up with a logical response to those questions, does your answer also respond to the program of the building in question? Does your idea fit within the budget? Does it mesh well with what the client desires? If not, should you try again, or did your principles send you off in the wrong direction in the first place?

There's a quote by Will Bruder in the January/February 2011 issue of Texas Architect (by the way, good article, Brantley) which I appreciated and which addresses this duality of principle and practice. He was speaking about two extremes: background buildings which have no aesthetic intentionality about them, other than accomplishing functional goals, and buildings by "starchitects" which are all about forms and shapes. I'll let him pick it up here:

"...architecture is not about that. It's not about being outrageous and radical, it's about the balance of poetry and pragmatism and when it comes out right, it is called architecture."

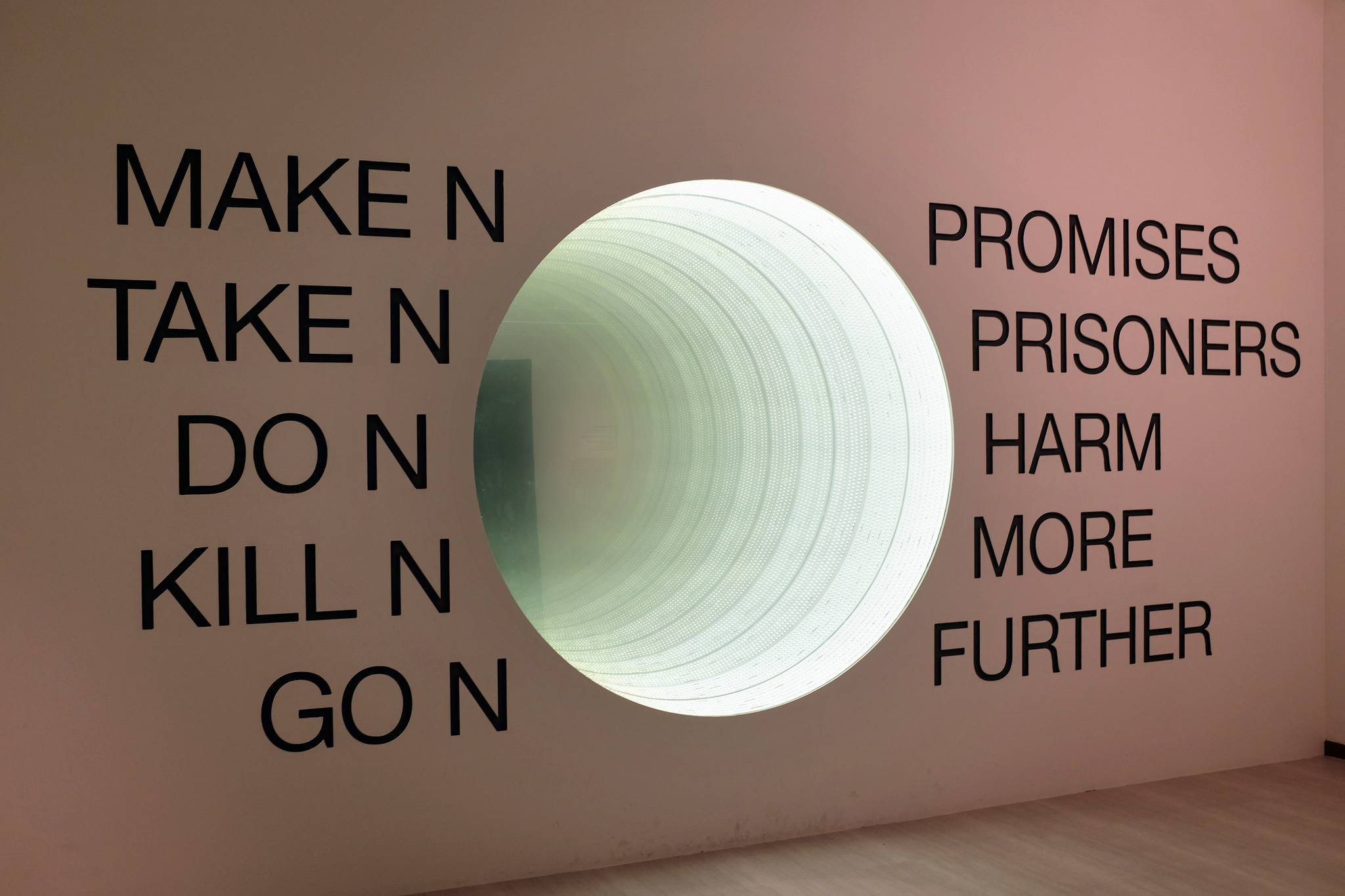

The 5 Principle No-s by Iswanto Hartono & Raqs Media Collective. Photo by Flickr user Jnzl at the Singapore Biennale 2013.

The 5 Principle No-s by Iswanto Hartono & Raqs Media Collective. Photo by Flickr user Jnzl at the Singapore Biennale 2013.

Brantley Hightower, 1/19/2011

I would say the implicit principle of most firms who are not subsidized by outside endeavors (or trust funds) is “get the next project”. Take our firm [Ed: Brantley's previous employer, not HiWorks] for example. While we have other principles that we like to talk about, that one about getting the next project has the strength to trump all others. While we typically practice an architecture that is “rooted to its place, responds to the natural environment and merges with the landscape,” if you happen to have a Spanish Mediterranean campus and no interest in sustainable building, we’ll gladly make an exception for you.

I realize that’s a cynical statement to make, but it is justifiable. As architects our ability to build things in the real world is always irrevocably tied to other people’s desires and money. This is where having strong internal principles can be an impediment to landing the commissions a firm needs to continue to exist and execute real projects according to their (now-compromised) principles. It’s a vicious cycle and I cannot solve it here.

All that aside, I whole-heartedly agree with your premise that work needs to have guiding principles. I believe a general set of principles should guide the body of work that is produced by a firm and I think a second set of more specific principles should define the goals for a particular project. In other words, any given effort should have a set of both strategic and tactical principles. The strategic aims remain consistent from project to project whereas the tactical ones change. That said the two sets should always be complimentary. This of course is easier said than done.

So, Jay, what are some overarching strategic principles you feel would be important to abide by in a hypothetical firm of your own creation?

Photo: Google Earth aerial of the University of Texas at San Antonio, a favorite example of a modernist campus turned Spanish Mediterranean. A look at the roofs in this image is instructive.

Photo: Google Earth aerial of the University of Texas at San Antonio, a favorite example of a modernist campus turned Spanish Mediterranean. A look at the roofs in this image is instructive.

Jay Louden, 1/22/2011

That question is kind of like "what is great architecture?" but in spite of its ineffability, it's a question that demands an answer. For me, part of that answer is like a north arrow on a compass (Part A), part of it is a perspective on management (Part B), and part of it is just completely made up (Part C). And all of it would change as soon as things are put in motion, because answers are only good until they're tested. I think that the question you've asked is at the very heart of what we do professionally and what we're doing with this blog, so I've marked out those parts with labels with the intention that we can return to each one (and others we identify) in subsequent posts -- it's too big to tackle without a great deal of back-and-forth.

So here are some initial thoughts on the guiding light portion of things, Part A. First, I think that great architecture contains a response to context. Unlike my favorite first-year design projects, it is not done in a vacuum. More than that, great design is arrived at by explicitly and intentionally considering the historical, physical, environmental, and programmatic influences on a given situation. But note that this is not to suggest that design is derivative, driven exclusively by those factors; it is as valid to consider and utterly reject context as it is to use context to shape the design like a grid on a sheet of paper. The intentionality of that decision is the key.

Second, I think this great design firm in the sky should approach technical questions with the mindset that there are new ways to answer old questions. This ties directly to one of our previous discussions [Ed: this one right here] about how current solutions to environmental control are poor. It is safe to accept previous answers, and undeniably risky to attempt new solutions, but for my own part, I'm really not interested in following.

Both of those principles are obvious, on a certain level, and I wouldn't think that (at least for us) there's a whole lot of controversy about them. While they need more development and refinement, the basic ideas are clear enough. But I think those two together only produce good architecture. There's a third, much murkier, principle which I think translates that firm into what we're both ultimately interested in, and I'm going to need help lining it out.

I'm going to start out by calling that third principle humanity. It's not a tangible kind of thing. I'm not even sure how to characterize it. But a project like the Kimbell has it in spades, and a project like Tadao Ando's museum in Fort Worth simply doesn't. It seeps from the cracks between the paving stones of medieval European cities like an affirmation of why life is worth living. It's present in a sidewalk cafe which was never touched by an architect, and completely missing in many of the white monuments of Modernity. It suffuses La Tourette but is nowhere in the grandiose La Ville Contemporaine. There's something about scale and materials and proportion and, frankly, kindness that touches on this principle. No, I don't own any all-black outfits, and I have no desire to. That is the opposite of this principle.

As an aside to this effort, I think it's unavoidable to consider how what we might think of as minimally architectural projects -- strip centers, suburban housing, doc-in-a-box offices, etc. -- fit into this theoretical space. Perhaps that's fodder for a future post.

Walt Stoneburner, Compass, photograph. May 2011. Via Flickr. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license.

Walt Stoneburner, Compass, photograph. May 2011. Via Flickr. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license.

Brantley Hightower, 1/24/2011

This blog is going to be incredibly boring if all we ever do is agree with one another, but I do feel that the principles you outlined are spot-on. Obviously we can debate the finer points of each of the three main principles you outline, but I think you did a good job of covering the bases.

I agree with the thesis you outlined in Part A: context is relevant. I think the particular education we received will prevent us from ever truly ignoring context - it must be considered even if it is not necessarily followed. That said it is my belief that "regionalism" as a driving idea behind design has played itself out in Texas. Perhaps it is fine as a point of departure but it's not enough merely to reference other materials and forms. Context must be used to propel a design forward, not hold it back.

That brings us to Part B: architecture is a progressive act. While characterizing a practice as experimental is usually the justification academics use to explain why their so-called firms have no real projects, I feel architectural ideas can only truly be tested when built in the real world. The trick here is that some experiments fail. Thus, finding an appropriate balance between taking risks in design and providing an acceptable level of service to any given client is critical.

That segues into Part C: architecture transcends building. This is what separates good firms from great ones. This is what you can't teach in school and, as you pointed out, is the most difficult to describe. I think I've mentioned before the phenomenon of walking into a noted building and thinking, "Well, this looks a lot like the photographs". That's a very different experience than walking into another building and thinking, "Wow, this is so much more. Why am I crying?" For me that has happened at Kahn's Kimbell Art Museum you referenced. It has also happened inside Sullivan's National Farmer's Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota.

In both the Kimbell and the Farmer's Bank, there is not one singular aspect of the experience that raises it to the level of the extraordinary. Rather it is a perfect balance between a symphony of discrete elements. Yes, light is important, but so too is color, composition, and an ultimately humane scaling of the space. Obviously there is more to talk about here, but ultimately the definition of this principle will be similar to the Supreme Court's definition of obscenity - it's impossible to describe but you know it when you see it. A more germane discussion might be to describe the design environment in which this end condition comes to exist. Both the Kimbell and the Owatonna bank were mature works of architects who had been honing their craft for decades (key to succeeding in this field is simple longevity since, with a few exceptions, there are no child-prodigy architects). They were also the results of close collaborations between a team of incredibly talented individuals. The Kimbell would be nothing without the structural innovations of August Komendant or the lighting breakthroughs of Richard Kelly. Similarly, it's hard to imagine the Owatonna bank without the ornamental flourishes of George Elmslie. In other words, the job of the architect isn't just to be a good designer, it is also to assemble a great design team.

Of course, if we define this last principle by studying these two buildings we might also conclude that good architecture must also prominently feature arches. Perhaps this should be Part D...

Photo of Louis Sullivan's National Farmer's Bank, by Tshearer at en.wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo of Louis Sullivan's National Farmer's Bank, by Tshearer at en.wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons