Introduction

A fair bit of the work we do involves working with historic buildings. This is becoming a more salient reality for many architects. Our cities are aging, downtowns are being revitalized, and there's more focus on keeping and building on what we have rather than wiping the slate clean and starting over.

Overall, this is a better place to be in than the giant block concrete buildings of 1972, but there are philosophical questions at the heart of work of this kind. What's worth keeping, and what should be discarded? What relationship should new construction have to old? When is something shallow mimicry, and when is it thoughtful and complementary?

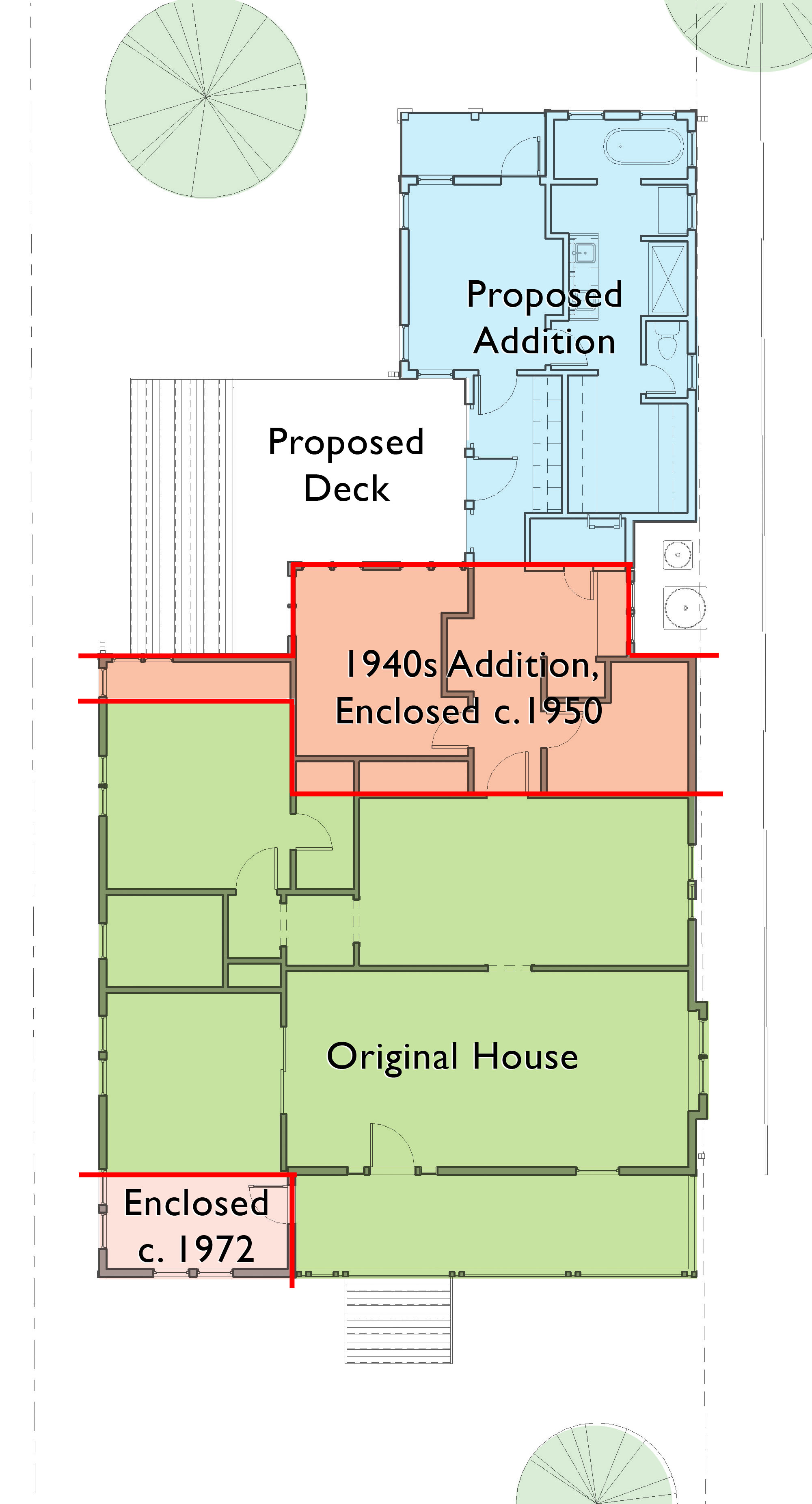

This article will look at a specific issue to illuminate two discrete positions: new additions to historic buildings. This is a project type we grapple with on a regular basis. It's a subset of a much wider field of preservation, and in discussing it, we'll elide a huge amount of theory and a great number of related (but tangential) issues in order to tackle the issue of new and old head on.

Take note, dear subject matter experts: this is intended for a general audience, so we will simplify the arguments considerably and invent some terminology along the way. Forgive us. We can have long, heated, alcohol-fueled discussions about the nuances of Ruskin's position on the fallacies of restoration, but for now, we're staying simple and clear.

Theory: Take One

So how do we approach a new addition to a historic home? Let's talk about theory, first. There are a couple ways of approaching how the new relates to old.

One option, which I'll call a historicist approach, is to carefully replicate historic appearances, including details, colors, and materials. The basic thought with this option is to design and build the work as closely as possible to how it may have been built at the time of the original construction. This perspective is, in some measure, nostalgic: it says that there's a truth in the original building -- and more specifically, a specific period in the life of the original building -- to which future changes must adhere.

This is a strict preservationist mindset, and it's the most common way to view changes to historic structures. It often boils down to solving technical challenges rather than theoretical ones, so there's much less interpretation and fluidity to this approach than the second. It can be codified relatively easily, though it's anything but simple to fit modern technology and expectations into a historic bucket. Nonetheless, most standards and design guidelines for historic preservation are built on this philosophical framework.

One problem, of course, is that the building wasn't originally built with that addition, or whatever the proposed project might be. It was built how it was built, and any change now is going to be divergent from its origins. Put less kindly, an addition which mimics the original too closely is lying about its origins and -- if you want to be mean about it -- mocking the history it's trying to protect.

So instead of pretending about history, why not accept that divergence and go from there? Well, that's option two.

Theory: Take Two

The second option (which I'll call divergent) is to use modern techniques and practices, to design in ways sympathetic to and coordinating with the historic building, but to specifically avoid copying historic practices. Window rhythms, overall scale, and other patterns may (frequently, should) be derived from the historic building, but detailing or materials might (again, frequently, should) be completely different. This second option can be thought of like a variation on a theme in a musical work -- different from, yet related to, the original thought. It's clearly a Modern (with a capital "M," referring to a specific philosophical approach to architecture) perspective. It allows for the progression of time in a way which a historicist approach does not, and it carefully avoids confabulating the history of the building. It sets out and separates what's old and what's new.

One big problem with this strategy is that it can be tremendously subjective. When things are more subjective, more decisions (and more critical decisions) must be made. When there's more room for error, inevitably, the disasters are bigger. The first option might fail on the side of boringness, while the second option might fail in a spectacular, and completely inappropriate, fashion.

It is also not what most people expect, so it frequently faces opposition. I.M. Pei's addition to the Louvre is the most famous example of this: rather than plunking down a neo-neo-classicist hunk of stone-clad concrete, which would have decimated the courtyard and greatly confused the historical narrative, he instead plunked down a glass pyramid which preserved the courtyard and historical narrative at the expense of greatly confusing pretty much everyone who isn't an architect (a certain type of architect, at that!). It appears, at this point, that Pei was on the right side of history, but that was no certain thing for a couple of decades. And, with as much as I've qualified that success, the Louvre work is an example which has turned out rather well, all things considered.

And, practice

I've sought to present the historicist and divergent options as diametrically opposed in order to express the theories behind them clearly. Truthfully, however, it isn't necessary to separate these two into completely separate, hard-and-fast schools of thought. In fact, any given design decision on a historic project is likely to fall along a spectrum between these two positions.

Let's again take a residential addition and renovation as an example. The historic design guidelines used by the city's Office of Historic Preservation and the HDRC point very clearly in a direction which is a synthesis of the two approaches:

1) Defer to the scale, massing, and articulation of the historic building. Tuck additions away on the back instead of slapping them on the front; don't add a second story smack on top of a one-story house, etc.

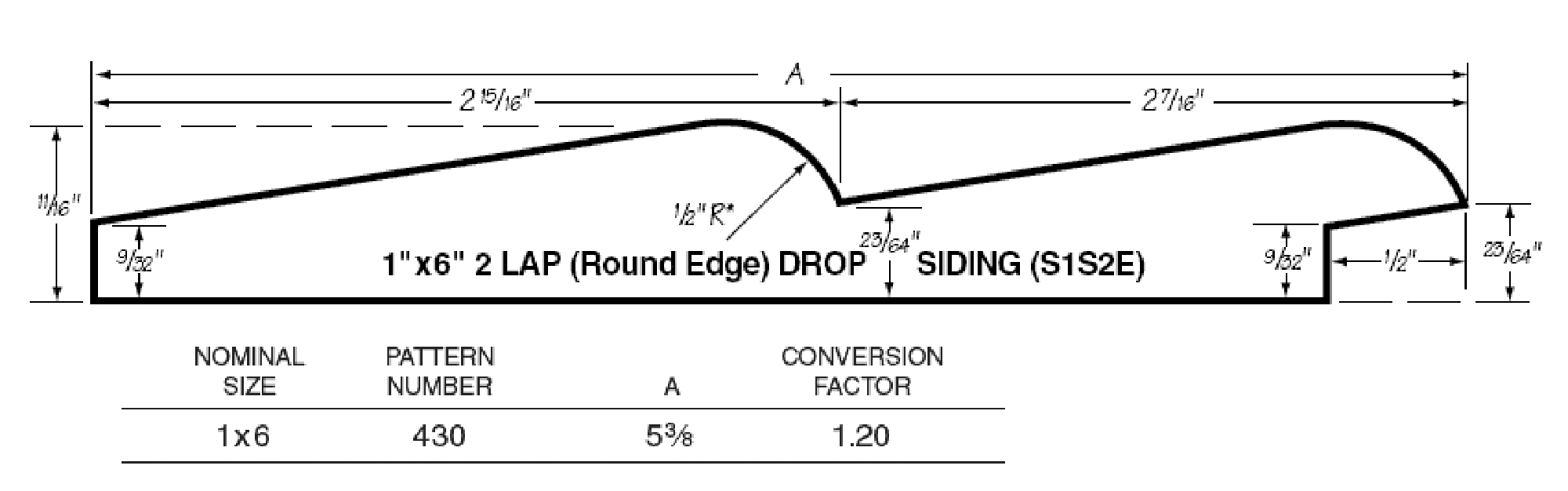

2) Use materials and colors which coordinate with the original materials (but which needn't be precisely the same)

3) Follow the general set of details for the historic building (like how trim, windows, and similar items were done) but don't try to precisely copy intricate detail (like gingerbreading, roof brackets, and the like)

It's an easy-to-follow, internally consistent set of guidelines, especially for the historic housing stock of the inner city neighborhoods. We follow these guidelines closely on our residential projects. For one, it's very difficult (if not virtually impossible) to get residential projects approved which do not follow the guidelines. More importantly, perhaps, is the realization that the intrinsic value of these neighborhoods is not in individual houses, but in the overall collection: the character of the neighborhood. Grandstanding on a house here and a house there does no service to the greater good of preserving neighborhood character. The city's guidelines are a very successful way of preserving that character.

Extension

But what if your project isn't so simple as that? What if you have an old warehouse, without significant historic context? What if what you want to do with the building isn't, you know, to use it for a warehouse, but to put a brewery and icehouse in it? The divergent approach allows us to support and maintain historic character while adapting to modern uses, needs, and materials. There are very high-minded, formal ways of doing so (many of Carlo Scarpa's works are tremendous examples of this) as well as more flexible strategies for modern insertions into a historic context (our own Pearl is a great model).

This is a tremendously more complicated and nuanced situation than a simple neighborhood-friendly addition. If you find yourself in this position, you should also find yourself a design firm which can tackle the philosophical challenges of adapting buildings but which also has the technical expertise to pull it off. *cough* Work5hop *cough*

Conclusion

We hope that's an approachable summary of one of the main theoretical divisions in historic preservation, particularly with how it relates to the realities of completing projects. If this has piqued your interest, we hope that you'll read some of the other articles on our website which deal with theory and practice. Here are a few to get you started: