Introduction

We believe that it's best to think about cities, and how they are run, as a means of improving the quality of life of all of the people who live in them. When mayors, city councils, and city staff make decisions about what kinds of development to support, or not, those choices affect cities: they change what choices we have for housing, transportation, recreation, and the level of city services that can be offered.

Cities are subject to the same overall financial dictates as any business, or indeed any household. Their sources of revenue are different – primarily taxes, rather than income from sales or a job – and their expenditures differ as well – roads, infrastructure, and services, rather than rent or groceries – but their overall finances must be balanced, just as we must manage our own personal budgets.

Because the primary revenue source for cities is tax revenue, how taxation relates to land use bears examination. Property taxes are of particular interest to us in this discussion, as the structural characteristics of land use and zoning directly impact that budget balance. How so? Cities provide infrastructure for development. Different types and densities of development require more or less infrastructure. But "more" and "less" in this case are not simple measures because of the impact of density.

Density and Infrastructure

Let’s examine two cases, using residential development as a model. Imagine that 50 households are moving to the city, and they need new homes. In one version of this reality, those homes are provided in single-family houses with a low-density residential zoning. We will assume 4,000 square foot lots per house, each of which is 1,600 square feet. In another reality, those homes are provided in an apartment building. It’s a large complex – we’re projecting the same 1,600 square feet per apartment as in each house.

The illustration shows these two scenarios. Notice the differences in infrastructure costs for the two developments. They’re substantially greater in the single-family scenario – five to one, in fact, or five times the cost – due to the larger land area, which in turn requires substantially more infrastructure to service. The bottom line is that less-dense housing is more expensive for cities to provide infrastructure and services.

Remember, though, this works just like any other budget: there are costs, but there is also revenue. What about the tax revenue side? There are differences there as well. Well, single-family home tax revenue is higher per acre than the medium-density residential tax revenue by a ratio of about 1.6 to 1 (see below for more explanation). That makes up some, but not all (or even most) of the differential.

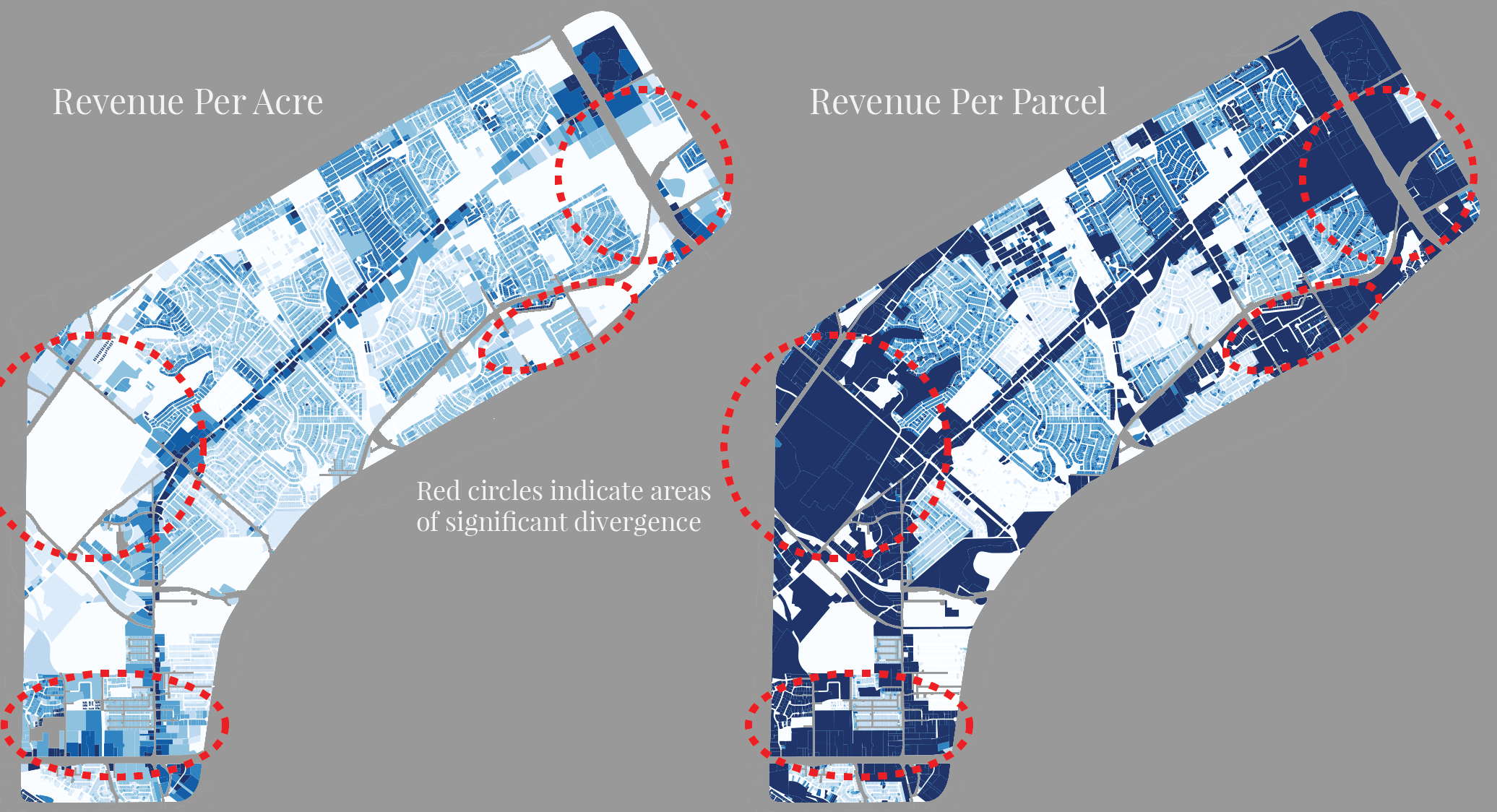

Tax Revenue Comparisons: Map

This plays out on a larger scale. These maps show a comparison between two ways of looking at property tax revenue: per parcel and per acre. The map on the right shows revenue per parcel, while the map on the left shows revenue per acre. The difference pointed out here is that large lots, while appearing to return significant revenue, are actually less efficient than smaller lots! This means that, for example, big-box stores even with their huge revenue, actually are less productive for the city than a similarly-sized collection of smaller retail operations. The red circles indicate areas where this differential is most apparent.

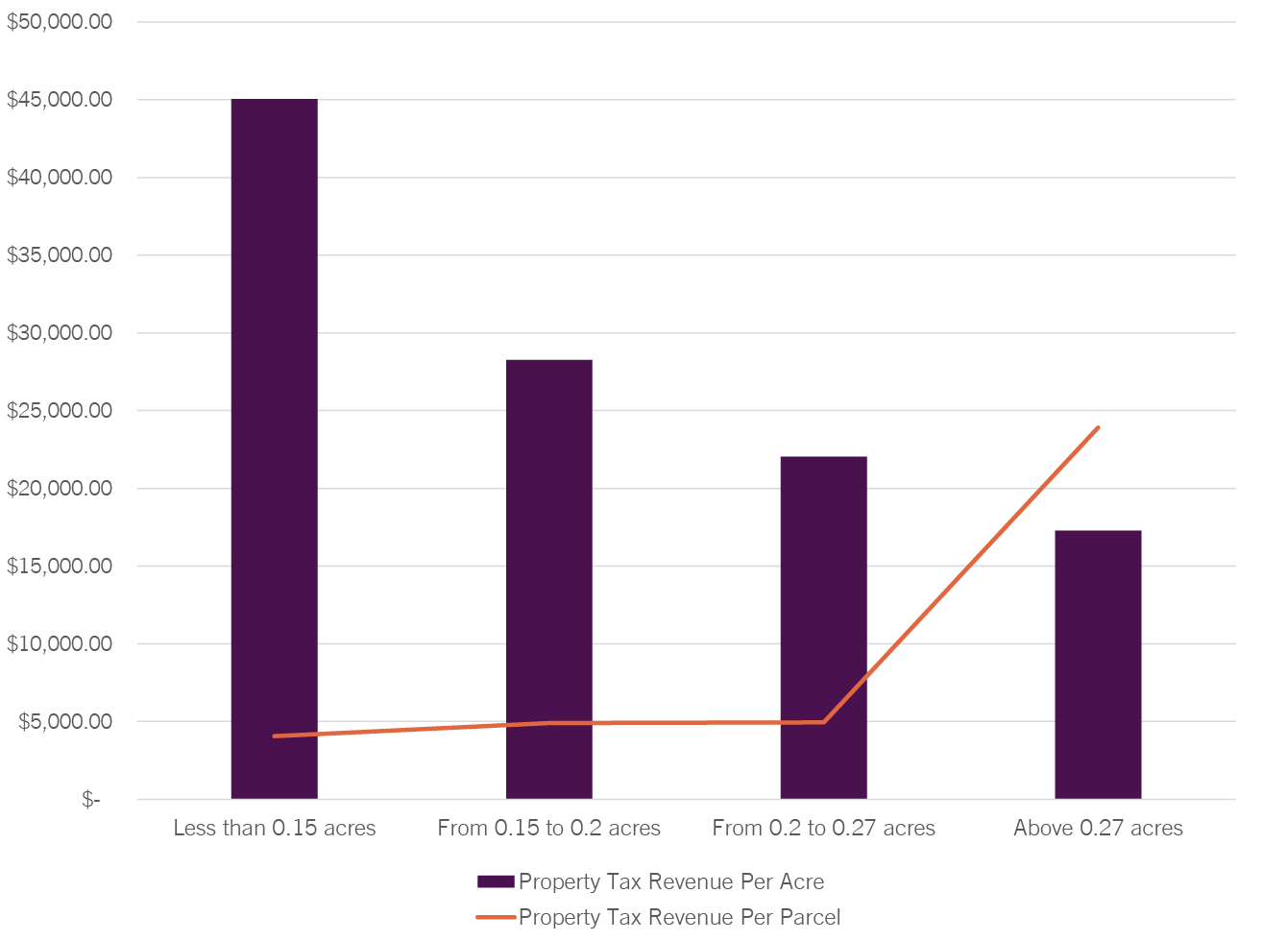

Tax Revenue Comparisons: Graph

This graph shows a similar story, reduced from the complications of land parcels to the clarity of numbers. This is two graphs in one: the purple bars indicate property tax revenue per acre, while the orange line shows revenue per parcel. The opposing trends are what is interesting here: the larger the parcel gets, the higher the revenue per parcel (which is a natural consequence), but the lower the revenue per acre. It is this conclusion which is most compelling for building a sustainable city. The graph says, in fact, that a one-acre area will return, on average, 1.6 times the revenue when split into six lots rather than one.

Conclusions

The conclusion from these findings – which is strictly a financial conclusion – is that more dense developments are financially more sustainable, because of the higher tax revenue per acre and the lower infrastructure costs per acre. In fact, depending on a number of different factors, many less dense developments operate at a deficit. That is, once maintenance and replacement costs are added in, developments less than a certain density never generate sufficient tax revenue to pay for themselves, at least at the level of city service which many people expect. Because city budgets must balance, those deficits are paid for by revenues which come from other places, not the least of which are property tax revenues from more heavily developed areas, like downtown.

This does not mean that there’s no place for lower-density development – far from it. Although city budgets must balance, we don’t operate our cities like businesses, which are tasked with extracting profit from operations and returning it to shareholders or owners. Instead, quality of life, diversity of experiences, variety in housing types, and myriad other factors are important considerations. What this does mean is that it is important to have density in cities and to incorporate land uses which create greater tax revenues. While this is sometimes opposed by neighborhoods, whose residents can view greater density as just more traffic and complication, that diversity of development type is critical to the financial sustainability of a city.